Almost every medical school in the U.S. hires what are known as standardized patients or SPs -- actors paid to portray patients who role-play with medical students. The job of an SP is not just to represent a patient in an accurate and realistic way, but to give feedback and insight to these future doctors about how best to communicate with patients. At its core, this job is a lesson in empathy for all involved. As an SP, I've learned crucial insights that allow me to better interact with my CF care team. To this day, I still use this new perspective to try to practice empathy with my care providers and myself.

Skipping Treatments Led to Fear and Guilt

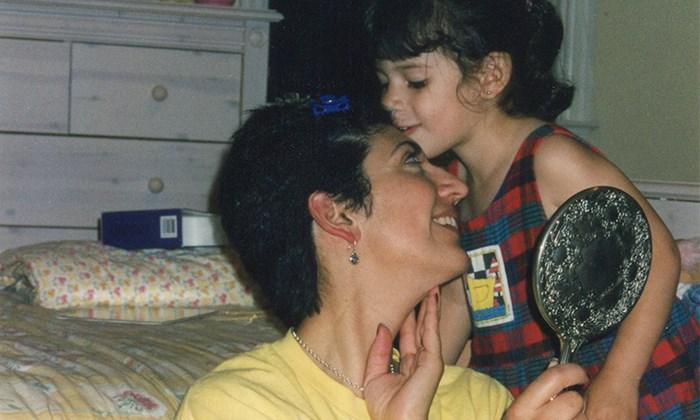

My mother, a nurse, told me that I was 3 months old when she began to suspect I had CF. One hot day while she was still on maternity leave, she tried to soothe my crying by kissing my forehead. My sweat tasted salty -- that was the first clear sign.

After other small hints -- my problems digesting food, for example -- and her many shifts at the hospital caring for and building close relationships with other CF patients, my mother felt justified in her suspicions. When she brought her concerns to my doctors, they did not believe her as I didn't fit within the more rigid norms of what a CF patient looked like at the time -- not white, not yet failing to thrive, and with no apparent pulmonary disease. My mother pushed back to no avail.

I continued to have problems putting on weight. By age 2, I was eating more calories than my father did in a day. Finally, we were referred to a gastroenterologist who was the first medical professional other than my mother to consider a sweat test, and I was officially diagnosed with cystic fibrosis.

My life was made easier by my mother's constant care and exceptional knowledge of the disease. Because of my significantly milder pulmonary symptoms, by the age of 10, I began intentionally skipping nebulizer treatments. Once I saw how little this affected me, I stopped taking enzymes. The practice of skipping treatments became habitual despite the abdominal pain it caused.

In hindsight, I see how this was my way of grappling with illness, making decisions more out of defiance and frustration than common sense. But my doctors didn't see it that way. Every appointment I was afraid of being lectured about not doing my treatments. I felt guilty too, knowing there were others with CF who couldn't just skip nebulizers without putting their lives at risk.

What Good Care Looks Like

The switch from a pediatric to an adult clinic can be difficult and strange. In my case, I was also in a new city going to a different hospital. I no longer had my mom to help me navigate conversations with my providers or advocate for me. But it was during this transition that I discovered my experience as a fictional patient provided invaluable lessons for me as a real patient.

Our job as SPs begins with trainings in which we learn about the patient we are portraying and the circumstances of the fictional scenario we will role-play. We read about the patient's medical history and personality. We map out a theoretical script that determines when we should give pertinent information to the medical student based on how the conversation is going.

For example, if a patient is scripted to be really nervous when talking about their symptoms, the SP must learn how to discern whether or not the medical student is making the environment safe and judgment-free. Is the medical student cutting off the patient as they try to talk? Or are they giving this patient lots of time to explain how they feel? Is the student asking leading questions that are dismissive? Or are they asking neutral and open-ended questions using appropriate and professional language?

This practice of discernment requires having a clear idea of what the patient's needs are and what good care looks like for that patient. As I got used to learning how to do this in a simulated setting, I realized how I was not nearly this intentional in my own clinic visits.

For me, two of the biggest barriers toward good care were rooted in issues with communication and assumptions. As a child I rarely felt heard or understood by my doctors. Instead of asking me why I wasn't taking my meds, my doctors sometimes belittled me. As a teenager I yearned even more to be treated as an adult, to not be talked down to or disregarded.

Starting at the adult clinic gave me a great opportunity to change this pattern and define what kind of relationships and care I wanted from my providers. Here are some of the things that define good care for me:

- Never being judged when I'm not able to prioritize my CF

- Making decisions collaboratively with my doctor (particularly regarding treatments and CF/life balance)

- Having opportunities to ask questions and educate myself about my illness

- Feeling safe to share sometimes embarrassing or difficult information

- Having gender-affirming conversations about sex and the social aspects of CF

- Being treated as a whole person -- not just a CF patient

Once I was better able to identify what good care looked like for me, it became a lot easier to tell when I was or wasn't getting it. I distinctly remember one visit with the nurse at my clinic in which I sat down and told her I really preferred that she called me on the phone instead of responding to my lengthy MyChart messages with one-line texts. My heart was racing; I felt so stupid making such a big deal out of it. But after that conversation, we had a much more comfortable and pleasant relationship.

Learning to Be a Better Patient

The CF clinic, or any doctor's office, should be a safe environment for you to address all your concerns, big and small; but sometimes the burden is on us to make room for that to happen by making the first step.

Since I started going to an adult clinic, my doctors haven't lectured me about compliance. There is no reprimanding, no shame, and no judgment, and this has been so empowering. But this new method of care had some unexpected downsides for me. I felt more alone in my care: There was no one holding my hand when I needed someone, and no one holding me accountable. I realized I wanted more explanation and more education from my providers, and I had to communicate that.

It also took me a really long time to start sharing issues about my social and sexual life with my new doctors. Growing up in an immigrant family, I often felt different from other kids with CF. I then went to art school, became vocal about my queer identity, and started making weird and sometimes highly political performance art. All these reflections on my identity felt incongruent with my limited idea of what the CF community was.

By constantly feeling other or different, I entered the clinic with the assumption that I wouldn't be accepted or considered a CF patient of priority. I thought that a few bad experiences of providers incorrectly making assumptions about my sexuality, my race, or knowledge of pertinent medical information would carry over into all my appointments.

One day, sitting with the adult CF social worker in her office, I finally mustered up the courage to say that I felt like I wasn't a patient of priority at the clinic because I wasn't “sick enough.” She looked me right in the eyes and asked me why I felt that way. It all flooded out: all the other CF patients who talked about perseverance and their many hospital visits; how terrible I felt knowing that, while not taking my own medications; the fear of being lectured at clinic; all the times the doctors couldn't look me in the eyes or talked to me as if I wasn't there.

She took it all in and said that being a healthier patient could be my strength. I had all these opportunities to do more of the things I love -- to make art, to travel, to write, to speak about my experiences -- and the CF community needed people like me to speak up and make ourselves heard. I carry this thought with me every time I talk about CF because it's a reminder that I, too, make assumptions and have to be open to thinking differently.

Empathy Is a Constant Practice

What I really have learned from being an SP and a patient with CF is that empathy is a constant practice of being open to the unknown and being willing to learn and make mistakes. The keen perspective I gained from thinking about patient advocacy in the SP setting has given me the power and the motivation to advocate for myself and the care I want, even when it's awkward and extremely uncomfortable.

It's also given me the strength to be kinder and more forgiving with myself. Instead of leaving the doctor's office beating myself up for not mentioning something that was bothering me, I now try to think -- why do I feel this way and where does this feeling come from? Instead of ruminating about all the times I could have worn my vest over the course of the day, I can honor what I did instead and convert what would have been wasted mental energy into the willpower to turn hypothetical treatments into real ones.

Join the conversation on Facebook.