The story of my relationship to my life expectancy probably sounds familiar to other cystic fibrosis patients. When I was born in 1988 and diagnosed with CF after an emergency surgery for meconium ileus, doctors told my parents that I would most likely not live past 18 years old. However, despite some difficulty with gaining weight that was resolved with the help of a devoted nanny, lovingly called “Tadi,” who spent hours feeding me, I soon started to thrive.

When I was 7 or 8, I stumbled upon a magazine from our local CF organization. I didn't fully understand, but I garnered enough from the article I had read to understand that someone's child had died of CF, at an age even younger than mine. I ran to my mother, crying in a panic, and asked if I could die from CF. She answered that nobody could predict when someone would die. These words, together with the assurance that I was doing really well “for someone with CF,” helped me push recurring fears to the contrary aside. Years of therapy later, I can reclassify seemingly unrelated childhood night-terrors and “irrational” fears of thunderstorms, fire, lights, sirens, appendicitis -- and later -- cancer (as I have written in another blog post), as the continual reemergence of fear I had denied: Having CF meant I would die young.

But I didn't know when “young” was.

When I was around twelve, my parents started taking me to a naturopath in another city. My naturopath, Manuela, also had CF and wrote two autobiographies about her illness and lung transplant experience. My parents bought the books and I secretly read them and -- as my parents, who tried hiding the books from me, had correctly predicted -- they utterly terrified me. Reading of the abrupt decline of Manuela's health in her early 20s convinced me that I, too, would suffer a similar decline around that age. The doctors who had told my parents I would die before age 18 had been right. When I reached my 18th birthday and nothing happened, I moved that imaginary threshold of life expectancy to 20, then to 25, and later to 30, haunted by the knowledge that I wouldn't live as long as my peers. To the inevitable “but you could be hit by a bus tomorrow” that people without CF usually provide at this point in my narrative, I answer: “Imagine you're walking blindfolded in the middle of the road and can hear the bus approaching -- you know it'll hit you, you just don't know when.”

Now at age 30, I have learned to relax, at least a little. I continue to see a therapist, though less frequently, and I try to concentrate on maintaining my good health (mentally and physically) and enjoy life with my wonderful partner, my adorable goddaughter, and work at my dream job as a junior researcher in disability studies.

Amid my attempts to enjoy the great and small joys in life, I'm faced with another problem. While studying some of society's expectations about people living with chronic or terminal illness, I have come to understand what I had instinctively known long before:

People think that, because of my reduced life expectancy, I somehow know more about the meaning of life than “normal people” and they believe that I live every day as if it were my last. Both expectations create a pressure that I have come to feel intensely.

If I should expect to die young, how should I live my life? How do I integrate the need to make the most of my short or shorter lifespan with the necessity to attend to the quotidian, the ordinary? As a fairly stable adult CFer, it seems I live with an endlessly deferred terminal illness. While CF is likely to kill me, I'm not yet in end-stage lung disease -- like Schrodinger's patient, I'm both terminally ill and yet not so. And I have no chance of getting out of this limbo, because -- of course, and thankfully so -- nobody can tell me when my current stability might come crashing down. It feels like drinking from a bottle of milk that has been in the fridge for a while -- without knowing the expiration date, you're always half-expecting a bitter aftertaste.

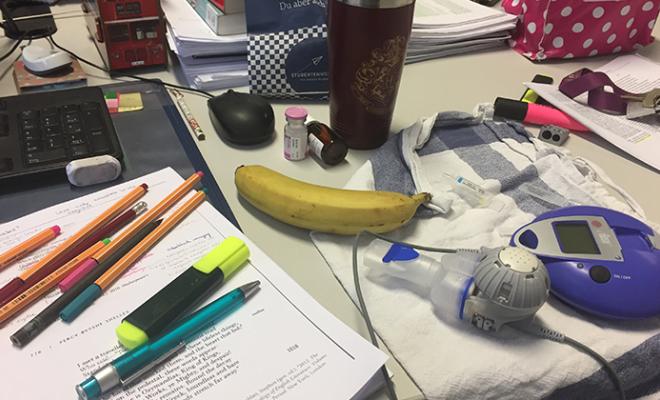

Contrary to popular opinion, my reduced life expectancy does not mean that I live a better life than others. Rather, society's implicit pressure of making my short life meaningful has contributed to my recurrent unstable mental health. Because, let's face it: I don't live every day as if it was my last. Perhaps not even every other day. Because I have a job. Because I need to cook, buy groceries, shower, file my tax reports, fold laundry, or correct mediocre term papers. Because some days, I'm so exhausted that I can barely bring myself to do my nebs before collapsing into bed. Because some days, I'm overwhelmed with fear and insecurity. Sometimes I'm struggling with grief over unattainable dreams and life goals that I have had to give up on. Sometimes I'm terrified that I'm running out of time and sometimes, when I look back on the many ordinary days that make up our lives, I become afraid I haven't tried hard enough to seize every day despite the fact that I'm living a good life, full of wonderful people for which I'm eternally grateful.

Living with cystic fibrosis means, at least for me, that I have to actively refute the idea that I could live every day as if it was my last. I'm not a terminal cancer patient with two months to live. I can't just quit my job and fly to Paris. I have to find a way to live with cystic fibrosis and the insecurities of my illness. So, I'm not always living my best life. And maybe, believing that I will have enough days left to make up for the ordinary, boring ones is the better mindset anyway.

Join the conversation on Facebook.