This blog discusses suicide and suicidal ideation, and some people might find it disturbing. If you or someone you know is suicidal, please contact your physician, go to your local ER, or call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-TALK (8255). The program provides free, confidential support 24/7.

I think the biggest thing I have learned from grief is that the perception of the future I have is an illusion. And that hurts every time.

For most, the last year has been riddled with grief of some sort. I have close friends who have lost family members; some are experiencing miscarriages, while others are ending relationships.

We are experiencing heavy personal transition within the turbulence, sadness, and separation of a pandemic.

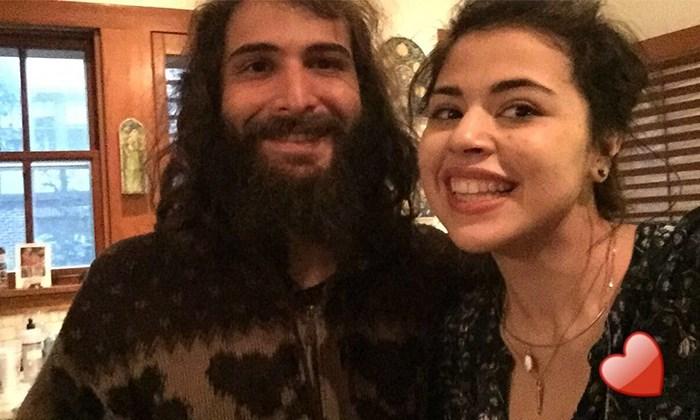

For me, I lost my favorite cousin Mason to suicide at the beginning of the pandemic; and within months, my Grandma died because of COVID-19.

I am learning we all navigate our grief differently in ways that our brains and bodies feel safe enough doing. For me, I didn't start feeling how earth-shattering Mason's loss was until about eight months after his death. I suppose I vacillated between denial and depression during that time. But, like a light switch, the grief that had knotted my body and brain was unleashed once my Grandma died. I woke up sobbing some nights, and my bones physically ached. Other days, I overreacted to small inconveniences.

Grieving isn't new for me. I have lived my life with cystic fibrosis -- a disease that reminds me daily of my mortality. I have lost many friends to CF, and each hospital admission or productive cough has carried its own mourning process. I have lost close friends without CF to unexpected and tragic death.

I thought I knew how to do this, but -- turns out -- I am learning more and more that grief accumulates and demands to be acknowledged.

When someone you deeply love (or heck, even an acquaintance) passes away, there is no “should have” or “could have.” There is only the conscious decision to choose to pick up the pieces and figure out how to wield them. I try to lean into my grief, like an old friend, and ask, “How are you?”

It can be vulnerable and uncomfortable to sit with my grief and feel what surfaces.

Inevitably, there's a deep want for some sort of connection with the person I lost, and I feel helpless. I sometimes bury this desire under distractions, hoping that I don't have to return to it. But, as I get older, I am learning that that approach seems to undermine the connection and bond I had with Mason and all the folks who have passed and deeply influenced me into being the person I am.

I've sat with the immensity of my loss and asked myself what is the best way I can go forward -- one that allows me to feel deeply saddened but not swallowed.

For me, grief is teaching me that it reflects my deepest fears, values, hopes, and love. Grief ultimately has taught me how fragile life is and the importance of being a genuine friend.

Picking up the pieces of my broken heart, I take these reflections into all my encounters. For me, connecting with others without hesitation seems to be an approach that helps the best. I have become good friends with a lot of my cousin's old friends, and I now let folks into my life with ease.

It's difficult to navigate what to say around someone who is grieving. But, there is something about the immensity and universality of the emotion that can allow us to become closer and more genuine with one another. When I act from that space, it seems easier to appreciate the uncertainty of living and the presence of another person.

Loss doesn't get easier, and I don't think it's meant to. It taps into core wounds and fears. I think we all have our own way of processing big transitions and losses. I think you can use your experience to remind you to live more mindfully and kindly, while holding space for others.

Interested in sharing your story? The CF Community Blog wants to hear from you.