Eating is supposedly easy. Most people would say it's too easy. At some point in history among privileged people, eating became less about survival and more about pleasure. Eating more than necessary, even at addictive rates, is normalized. Yet, we also worship those who abstain from carbs and fats with awe-inspiring tenacity to grace the pages of Vogue and Elle.

So, perhaps I shouldn't be surprised when people respond to my weight-gain struggles with a longing gaze and the familiar joke: “Wow! I wish I had that problem.” I usually respond with some awkward blend of a chuckle and a sigh. Malnourishment isn't funny.

Many people envy the slender ones with cystic fibrosis who have pancreatic insufficiency, which is characteristic of about 85 percent of CF cases. That insufficiency makes it difficult to digest food and absorb nutrients, like fat and protein. In addition, there are the common CF complications, like constant nausea, crippling delayed gastric emptying (food staying in the stomach too long), severe reflux, and taste-morphing medication side effects. The rotten cherry on top of this sundae is that -- despite all those obstacles -- some people with CF need double the amount of calories that a healthy person needs because of the caloric bonfire being fed by sieging lung infections and heavy breathing. It's all a recipe for weight instability that can dwarf even lung problems.

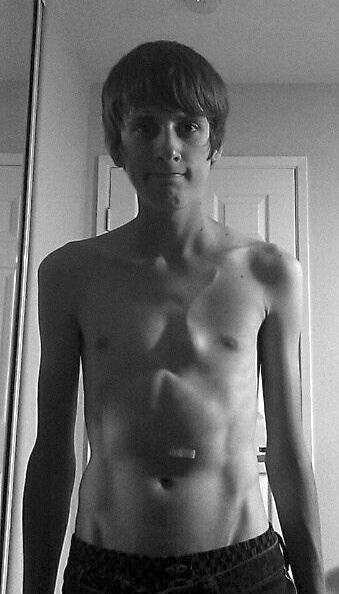

But, CF is an invisible illness, so most people typically don't have a clue what batters a person with CF every day. Some friends saw me as healthy because of my skinniness, not knowing there were days that being nutrient-deprived kept me pinned to my bed in the morning.

Friends fantasized about eating whatever they wanted “without consequences,” not knowing that, for me, it felt like iron weights were dragging down my lower jaw, while I crammed crumbles of food into my mouth. They didn't know that chocolate cake tasted like dirt or that pancakes tasted like cardboard. They didn't know I'd spend more than an hour focusing on consuming just 500 calories, only to end up hovering my tear-streaked face over a vomit lake in the toilet.

Eating wasn't always so challenging. I once loved food so much that I wrote restaurant reviews for my school paper and aspired to be a chef. But, my progressive lung deterioration gave root to many of the aforementioned digestive complications. Rather than practicing cooking, I watched hours of the Food Network, gazing at videoed food and hoping that my appetite would reignite. Sometimes it'd work, sort of, but after a single nibble, my body would reject the food; a mental barrier prevented me from stuffing it down my throat.

It was demoralizing in ways incomprehensible unless you've experienced the same. That's the thing about appetite loss. There's the misconception that it always means a person doesn't want to eat. But, I desperately wanted to eat. I just … couldn't. My taste buds and stomach didn't connect with my brain.

Getting a feeding tube in the 10th grade felt like the ultimate failure at the time. It was another step into being swallowed up by the medical world. For eight years, each night before bed, I poured five cans of Nutren 2.0 -- which is kind of like Ensure®, but with an even more delicious-sounding name -- into a bag, then hooked up the line from the bag into my feeding tube. Forty-two ounces of liquid fat dripped into my stomach as I slept. I took in 2,500 calories, 115 grams of fat, and 105 grams of protein per night, yet I rarely gained a pound.

I felt defeated. My feeding tube was artificially providing something that humans should instinctually crave. Doctors labeled my malnourishment as “failure to thrive.” That phrase has fallen out of usage, but it took a heavy toll on my psyche: Eating is an instinctual necessity, so life without food is life without a necessity. When the body doesn't crave food, it doesn't crave life. That thinking is flawed, but it wedged insecurities into the corners of my mind.

I received a double-lung transplant in January 2017. Since then, I've weaned off of my feeding tube and now have an appetite that is charged by prednisone and an active life. Friends now laugh about how much I eat and post food pictures to my Instagram feed.

While I still struggle to gain weight, at least I'm struggling without relying on a feeding tube. As much of a lifesaver as the tube was for me, I don't miss it.

When people ask what my favorite part of post-transplant life is, I often respond that it's being able to eat enjoyably and without nausea. They think that's absurd. But, if they barfed every day and their food tasted like dust for several years, too, maybe they'd agree.

If your loved one with CF struggles with weight, have sympathy. Remember it's not a problem they feel lucky to have, and mere mentality does not always remedy it. Eating isn't easy for everyone.