Scrubs to hospital gown

Being a nurse with cystic fibrosis has presented some interesting realizations and opportunities in my adult life. When I was a new nurse, I often dealt with imposter syndrome, thinking, “Will my patients catch on that I’m actually just a patient too?” With a few more years of experience, I learned to harness both identities as a superpower, which helps me to be a better advocate for my patients, as well as for myself; it hasn’t come without challenges.

I’ve been a nurse for 10 years and the dichotomy of the overlapping identities of nurse and patient continues to permeate my life. It’s one thing to be a nurse speaking up for her patients, and quite another to be the patient knowing how and what to do in times of uncertainty, disease progression, and survival. It is within the halls of hospitals where I have experienced the most deeply formative moments in both my personal and professional life. Even so, being a nurse doesn’t mean I don’t struggle with being heard and advocating for myself.

Worthy of the fight

Cystic fibrosis patients are a unique breed in the medical world. Since most CF patients are diagnosed early in life, we tend to have more familiarity with the health care system and communicating with doctors and care teams than the average person. We learn young that if we don’t communicate effectively, our physical bodies can suffer and — as a result — we are prevented from doing the things that really matter to us in life. We all know life is far too short to allow that.

Only I can communicate what I am feeling in my body. Only I can give the most accurate history and description of what is going on. We all know tests don’t show the whole picture, and sometimes we can tell something isn’t right before a pulmonary function test (PFT) or lab test can pick up it. You are your own best advocate.

I don’t think I have met a fellow CFer who hasn’t passionately fought for their own health (and life) at one point or the other, so I may be preaching to the choir here. But, hopefully, I can share some helpful insights from my own experiences.

Self-advocacy defined

Advocacy is focused on a patient’s right to make decisions about their health care with their quality of life, dignity, and equality upheld at the center. Self-advocacy, then, is the self-motivated choice to be an active participant in one’s own health care. This means engaging with my care team consistently to ensure that you get the care I need when I need it. Self-advocacy is not meant to be a “doing it all myself” approach, rather a partnership between my care team and me. The end goal of self-advocacy is about making sure my priorities are met, symptoms are managed, questions are answered, and ultimately that I feel my care is centered on what matters most to me.

The challenges

Not breaking news for anyone, but there are, and will be, inevitable barriers that we encounter in our care journeys. What’s important is identifying what the challenges are and knowing how to press in, utilize resources, and not let them stop me from receiving the care I need.

One of the most challenging things I’ve had to learn is that my voice matters. For a long time, I just listened and “obeyed” the doctors because they were the ones with the knowledge and authority. I have learned that I can be a leader in my care, and that my voice and input can and should be of equal volume and value to that of my care providers.

Here are a few potential barriers that can impact the care we receive:

• Education level

• Health literacy

• Racial/ethnic inequities

• Access to health care

• Income

• Age

• Language

• Perception of self-worth

When we as patients and I don’t or can’t use our voices to self-advocate in an effective and proactive way, we may feel confused about what’s happening; don’t know how to manage symptoms; are less likely to stick to our treatments and have poorer outcomes; and, ultimately, our quality of life can suffer.

We need to be aware of what our specific barrier(s) are or could be so they can be addressed and not prevent us from receiving the care we need. We need to remember that we are the most important member of our care team.

Actions in advocacy

One of the most difficult lessons I’ve had in prioritizing my health was deciding to stop working at the age of 27. For four years, I had pushed myself so hard, doing everything within my control to make work, work. I was clinging to a sense of normalcy in a job I loved, but my body only grew weaker, and it took a toll on my lungs. I have since learned the tremendous importance of preventing decline by stopping when my body says stop. I’ve learned that one of the most proactive ways I can care for myself is by listening to my body and slowing down when it advocates on my behalf through symptoms. I’ve learned that success is not found in a job; success is found in doing whatever is necessary to care for myself so that I can live the kind of life that is most important to me.

The five Ps of self-advocacy:

- Prioritize what matters to me. Get clear on what my values and quality of life goals are. Start the conversation. (Think holistically: physical, emotional, mental, spiritual.)

- Be proactive to prevent problems within my control through effective communication. I know I am communicating effectively when what I communicate is heard, understood, and followed up with appropriate action and that my needs, values, and priorities are translated into the care I receive.

- Be a partner, not a pawn with my medical team. Research, ask questions, know what to expect so I can report problems. Know I always have a choice and permission to change plans, interject, and be an active participant in my care. Utilize resources like the people on my care team that want to support me i.e., the nurses, social workers, dietitians, financial counselors, and pharmacists.

- Know my people, and make sure my people (i.e., family, friends) know my values, goals, and priorities in care. I also find strength in my support system.

- Believe my voice is powerful, and I am worth the fight.

Gaining strength through my support system

Asking for help can be one of the most difficult things for us humans. I realized it’s important for me to find my people – the family or friends whom I trust and aren’t afraid to ask for support. Asking for and receiving help can be deeply humbling and deeply comforting from an emotional and practical standpoint. Even delegating tasks to loved ones, like picking up prescriptions or making phone calls, can help so much. Many times, I have attempted to do everything myself with the result of feeling more burnt out and even more alone. Don’t carry it all on your own and don’t suffer in silence!

I’ve found it’s important to communicate my values, needs, and priorities with my loved ones. This includes making sure that the person(s) I choose to be my medical decision-maker(s) -- in the case where I can not speak for myself -- knows my quality-of-life goals and end-of-life wishes, such as life support and organ donation.

Last, I find support by connecting with other CF peers through my clinic, virtual support groups, or social media. I still go to my friends with CF to talk through symptoms, medications, and navigating post-transplant life. Even as a nurse, I need the support of my CF peers to validate my experiences and to know I’m not alone in it all.

If I don’t have a voice

About six months after my double-lung transplant, I developed some pain in my left hip. After a couple months of rest and stretching, the pain only seemed to get worse. Three different doctors told me it was likely just a stubborn case of bursitis (inflammation of the hip joint) from overuse. It made sense to me since I had recently started working out again, so I tried my best to rest and ignore it.

Three months went by, and the mild hip discomfort turned into severe, aching pain to both hips and my lower back — in addition to some crazy fatigue. Looking back, I have no idea why I didn’t shout to my doctors “I’m in excruciating pain!” But since I had been told multiple times that it was “just bursitis,” I pushed it off and told myself it would go away eventually. It’s amazing what those of us living with chronic illness or pain tolerate — uncontrolled pain or feeling miserable should never be “par for the course.”

After almost three months of enduring this pain, I developed a fever and headed straight to the ER. The focus quickly became running “all the tests” to find a possible source of infection. Self-advocating in that moment sounded like telling my nurse, “I know the fever is not great and all, but what’s worse is this crazy pain I’ve been having in my hips and back.” I was weak, out of it, and vulnerable, but I spoke. That comment led them to do an MRI of my back and hips where they found lesions in both femurs and my spine. The lesion on my left hip was growing outside of my bone, causing a small fracture. A full body CT scan was next, and it showed more lesions in my liver and abdomen. The plan was to do a liver biopsy to diagnose the cause.

Up until that point, I had been in the ER by myself. With this news, I knew I needed support. My family lived out of state at the time, so while they arranged flights, I called one of my best friends and asked if she could come be with me. She dropped everything and headed straight to the hospital.

What should have been a routine liver biopsy quickly turned into an emergency when an artery was nicked causing internal bleeding. As soon as I was rolled back to my room, I knew something was wrong. I looked my friend in the eyes and told her I needed help. The nurse called a rapid response, and the rest was a blur. My friend was able to give them important information about my wishes and health history and she called my family to urge them to get there as soon as possible.

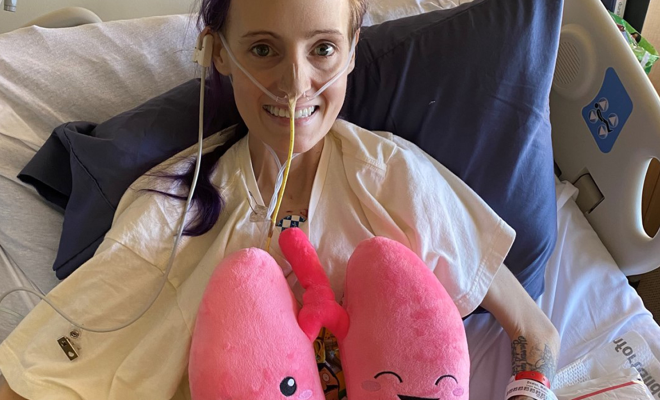

Recovering in the ICU, I learned that the biopsy showed that I had a post-transplant form of cancer called post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder, or PTLD. PTLD is a type of lymphoma caused by being too immunosuppressed after a solid organ transplant.

I thought to myself, “I am an oncology nurse. I treated lymphoma patients. And now, I am the oncology patient.” My life had been turned upside once again in the ongoing backwards game of nurse to patient.

Sometimes no matter how prepared, informed, or proactive we are, life can still bring the unexpected, through no fault of our own. No matter how perfect we stick to our treatments and do our part, some things are out of our control. At the end of the day, we all need support and connection, and we all need to be compassionate with ourselves through all the ups and downs.

At the end of the day, it is the belief that you are worth the fight that will empower you to advocate for yourself most effectively.

Interested in sharing your story? The CF Community Blog wants to hear from you.