Personalized medicine -- also called precision medicine -- has received a lot of attention in the past year, including a mention by President Obama during the annual State of the Union address in January. But what does it really mean for people with CF? In the opening plenary session at NACFC, John P. Clancy, M.D., professor and director of CF Clinical and Translational Research at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, discussed just that.

The idea of personalized medicine is nothing new. It is practiced at CF care centers every day. Based on their specific needs, individuals with CF are prescribed medications and therapies, such as antibiotics, pancreatic enzymes and airway clearance therapies. But more and more, personalized medicine is beginning to have a new meaning.

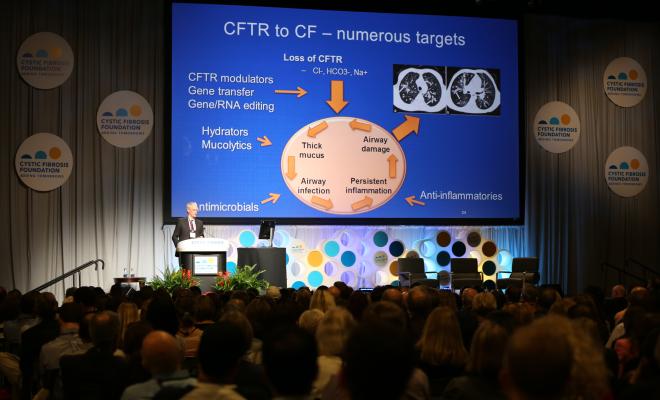

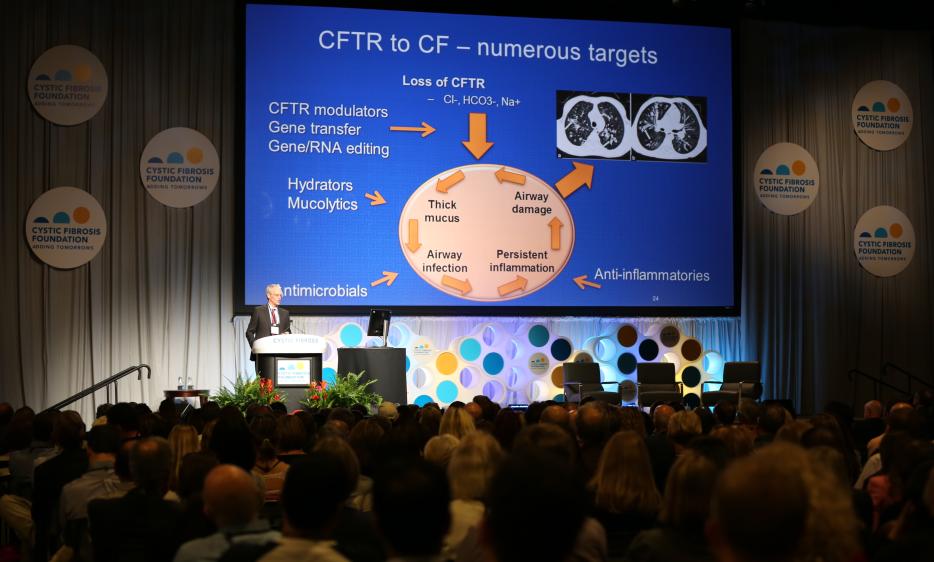

With the recent development and approval of the first drugs that target the basic defect in CF, an abnormal CFTR protein, the idea of personalized medicine means understanding an individual's underlying genetic problem and treating it directly.

Clinical trials of ivacaftor (Kalydeco™) in people with G551D and other rare mutations clearly showed that drugs that target the malfunctioning CFTR protein at the cell surface have the potential to greatly improve health outcomes, including increased FEV1 and decreased exacerbations. Major clinical trials of the ivacaftor/lumacaftor combination (Orkambi™) also showed significant improvements in people with two copies of the F508del mutation, with the drug helping the CFTR protein get to the cell surface and function properly.

However, we have also learned that drugs targeting CFTR protein can result in a range of responses, with some individuals showing significant clinical improvement while others have little to no response.

The range of responses highlights the need to find ways to determine who will benefit from a specific therapy. Dr. Clancy explained how we've already started to do this, and where we can go from here.

Researchers have developed ways of creating so-called model systems, essentially cell samples taken from the nose or other area of the body of an individual with CF. The hope is that doctors will be able to take a cell sample from an individual with CF, expose it to different drug compounds and then decide which drug would benefit that person the most.

These model systems are still being tested, but they represent just how customized care could become once a broader range of drugs becomes available. Dr. Clancy emphasized that once therapies are prescribed, it is important to monitor their effectiveness to ensure they are delivering the best results for the individual. It is also important to remember that CF is a multi-organ disease, and the effectiveness of treatments in parts of the body besides the respiratory system needs to be evaluated to understand their true impact.

In the coming years, we hope that doctors will have an arsenal of new therapies at their disposal to help provide the best care and treatment options for individuals with CF so that they can live healthy and fulfilling lives. In this new era, doctors will be able to use information about a person, including his or her specific CF mutations, lung function and bacterial infections, to select from a number of therapies to determine the best treatment options.

It is encouraging to see how the progress of drugs that target the underlying cause of CF has changed the lives of so many living with the disease. Walking out of this plenary, I am even more excited to think about the potential that these therapies and others in development have for improving the lives of individuals with CF in the near future. Personalized medicine at its finest.

If you did not have the chance to watch this plenary live, watch a recording of the first plenary here.