In 2017, I sat nervously in a windowless room at the hospital during transplant education day, listening to a nurse recite the names of all the new medications required after a lung transplant. The list was filled with unfamiliar drug names in a variety of categories: antivirals, antifungals, antibiotics, and of course, anti-rejection medications. The nurse made it abundantly clear that transplant wasn’t a cure for cystic fibrosis, but the trade-off of one complicated medical problem for another.

This much I understood, and I took her warning to heart. I already knew how to be sick, I reminded myself. I’ve been doing this for 40 years. At the time, my lung function hovered stubbornly around 22% while I struggled through hours of exhausting breathing treatments and inhaled nebulizers each day. My energy level was low to non-existent. Tethered to supplemental oxygen, losing weight, and coughing up blood without warning, I felt my world shrinking at an alarming rate. Who knew what lay on the other side of transplant? Better health? New medical problems? I thought I was ready for anything.

As it turns out, much of the transplant experience took me by surprise, and in time I found myself struggling with the most basic of concepts: trying to shed my illness identity in favor of embracing wellness and health.

It shouldn’t have been that hard, right? It wasn’t as if I wanted to feel sick! But there is an enormous amount of soul searching that happens after undergoing as dramatic a metamorphosis as transplant. It was an emotional roller coaster unlike anything I had ever experienced.

Startlingly, the grief I felt for my donor post-surgery was intense and absolute. Whether it was the magnitude of what had just happened or the high doses of steroids pumped into my system, I deeply mourned the person who had lost their life just as I regained my own; whose family unselfishly fulfilled the wishes of their loved one while my family celebrated my “rebirth.” The unfairness of it all and the survivor’s guilt wrecked me — and if I’m honest, it still does. But I had made one crucial decision well before my transplant. I asked for help.

Professional therapy changed the way I responded to anxiety surrounding my illness, but not without revealing truths about myself that I had been unwilling to face. Like it or not, I had developed an illness identity over time. Having a chronic illness was inextricably tied to my sense of self, and “sick” was a role I played out of habit. I disliked sleepovers as a teenager because the thought of doing treatments in front of friends terrified me. I went to college close to home so I didn’t have to change my care team and leave my support system. I even pushed myself to study abroad my junior year, but I picked England instead of my first choice, Italy, because being in the U.K. gave me better access to CF care. Every decision I made in life had cystic fibrosis at the forefront; and though you could argue that these were thoughtful decisions made with my ultimate well-being in mind, they also contributed to my identity as a person who couldn’t (or wouldn’t) take risks.

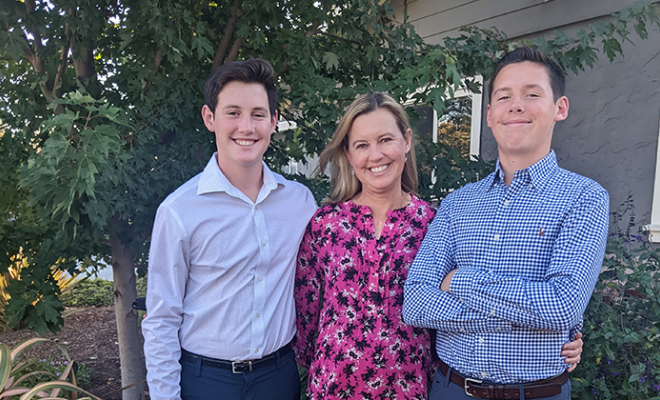

My therapist challenged me not to accept the role of “sick person,” and to embrace the idea that although my illness had shaped me, it didn’t have to define my future. She reminded me that in marrying my husband and welcoming twin boys into the world, I had already taken risks that enabled me to invest in my future. Cystic fibrosis would always be part of my life, she said, but I was here, and whole, and I had a life to lead.

But making the leap from being near death to believing I was in good health seemed like too great a barrier to overcome, even post-transplant. If there’s anything cystic fibrosis has taught me, it’s that the other shoe always drops.

It seemed to me that anytime I enjoyed reasonably good health, an infection would send me spiraling into the hospital. How many of us are afraid to admit we are feeling good, as if saying it out loud might jinx the tenuous hold we have on wellness?

Even researchers have noted that a strong illness identity is a legitimate predictor for more hospitalizations, not less. I am reminded of a quote from a mental health podcast I once listened to: “There is nothing the mind cannot do to the body.” As a chronic illness fighter, I have to remind myself that I can’t grieve poor outcomes in advance. Coping isn’t about imagining all the worst-case scenarios so I am “prepared” for bad news. Hopefully, it’s about appreciating what I do have, and letting moments of joy exist independently of my health status.

My post-transplant identity feels different from my pre-transplant self. I no longer feel as if I am on a path of slow, inevitable decline. But from the day I received the precious gift of new lungs, just as that nurse predicted, I have faced a host of other medical issues. I needed two more major surgeries to remove scar tissue from my chest cavity. I developed a leaky heart valve that requires regular follow-ups with a cardiologist and could lead to more surgery. I was diagnosed with post-transplant lymphoma; unfortunately, cancer is often the unintended side effect of taking immunosuppressant drugs. All of these things happened even before the COVID-19 pandemic added another layer of fear and uncertainty to my life. But in between these lows, the highs have been hard to beat. One year after transplant, I ran my first 5k race in years. I started hiking regularly with my husband, riding bikes, and playing tennis with my boys, and traveling with my family. I was still fighting medical battles, but this time I could recover and continue building memories.

I know now that the most certain thing about transplant is the uncertainty. The constant ebb and flow of health, the accomplishments and the failures, and the specter of rejection always make for dramatic highs and lows in this very surreal life of breathing with somebody else’s lungs. Each year on my transplant anniversary, my therapist asks me the same question: “Are you healthy?” For years, I couldn’t bring myself to say yes. “But I just had another surgery/diagnosis/setback,” I would tell her. She gently reminded me that in the meantime, in the beautiful in-between, I had much to be grateful for. As my fourth transplant anniversary approaches, I think I might be ready to break the pattern of letting my health define me. I still have cystic fibrosis, post-transplant medical issues, and so many uncertainties. But I’m here, I’m whole, and I’m trying, and that’s healthy enough for me.

Interested in sharing your story? The CF Community Blog wants to hear from you.